What the drunk doesn’t know is that you are trained in the Indonesian martial art silat, and you are therefore able to move easily into close range where your big guns—the knees, elbows and head—can be brought into play. This range is referred to as the “battleground” by Indonesians.

Now that you’ve entered the battleground and are literally in the drunk’s face, you can begin the “tranquilizing process”—a vicious combination of elbows, knees, finger jabs, head butts and kicks to his groin, shins, thighs, eyes or any other vulnerable target. If he is still a threat after your initial salvo of blows, your combinations must continue. Can you sweep him to the ground? Can you elbow his spine? Can you stomp on one of his feet and force him off-balance? These are just a few of the possibilities available to an accomplished silat stylist.

What Is Silat?

Roughly speaking, silat means “skill for fighting.” There are hundreds of different styles of silat, most of which are found in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, southern Thailand and the southern Philippines. Common to all of these styles is a combat-oriented ideology and the use of weaponry.

In Indonesia, there exist hundreds of styles of pentjak silat, as well as many systems of kuntao, a form of Chinese boxing that bears many similarities to silat and is found primarily within the Chinese communities in Indonesia. There are also many systems that blend pentjak silat and kuntao.

“Chinese fighting tactics have had positive influences on the development of pentjak silat,” says noted martial arts historian and author Donn Draeger. Malaysia is home to a style known as silat, which can be divided into two forms: pulut, a dancelike series of movements intended for public display, and buah, a realistic combat method never publicly displayed.

Silat is also found in the southern Philippines, as well as langkah silat, kuntao silat and kali silat. Silat techniques vary greatly, from the low ground-fighting postures of harimau (tiger) silat to the high-flying throws of madi silat. One particularly vicious madi throw involves controlling your opponent’s head, leaping through the air, and using your body weight to yank him off his feet as your knee slams into his spinal column.

A typical harimau takedown involves coming in low against an opponent’s punch, capturing his foot with your foot, and forcing his knee outward with a strike or grab to the inside knee to effect the takedown.

Rikeson silat focuses primarily on nerve strikes, while cipecut silat makes extensive use of the practitioner’s sarong for throwing and controlling the opponent. A rikeson silat stylist might take an opponent down with a finger-thrust attack to the nerves situated in the crease between the upper leg and torso.

Cipecut practitioners will deflect an attack with their sarong, then wrap it around the opponent's head, utilizing the significantly improved leverage to yank him to the ground.

Bukti negara pentjak silat, as developed by Paul de Thouars, relies on a sophisticated leverage system to achieve almost effortless throws.

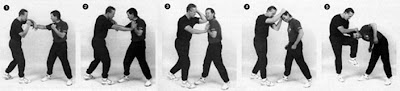

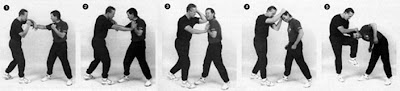

In this self-defense sequence, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) scoops (1) his opponent’s jab and simultaneously traps (2) his foe’s other hand in place. Gibson is now free to deliver (3) an elbow to his opponent’s face. Gibson then grabs (4) his adversary’s hair with both hands and pulls (5) his head into a knee smash. (Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

In this self-defense sequence, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) scoops (1) his opponent’s jab and simultaneously traps (2) his foe’s other hand in place. Gibson is now free to deliver (3) an elbow to his opponent’s face. Gibson then grabs (4) his adversary’s hair with both hands and pulls (5) his head into a knee smash. (Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

In Philippine silat, it is common to trap your opponent’s foot with your own foot while controlling his head and arm, then spin him in a circle. The opponent’s body rotates 360 degrees, but his knee and foot remain in place, causing severe injury.

The sheer number of silat styles allows practitioners a tremendous amount of variety, as well as a certain amount of freedom and self-expression. By researching a number of silat systems, you can add tremendous diversity to your combat arsenal.

Weaponry

Virtually all silat styles, particularly Philippine silat, emphasize weapons training. In the areas where silat originated, carrying a weapon, usually one of the bladed variety, was for generations a fact of life for the general male populace. A silat practitioner will normally be skilled with a knife, stick, sword, staff, spear, rope, chain, whip, projectile weapons or a combination thereof.

The keris, with its wavy blade, is one of the most common weapons in Indonesia and Malaysia. Another wicked weapon found in Indonesia is the kerambit (tiger’s claw), a short, curved blade used to hook into an opponent’s vital points. According to Draeger, the kerambit is used in an upward, ripping manner to tear into the bowels of the victim.

Most silat systems emphasize low, quick kicks, primarily because of the likelihood the practitioner will be confronting an opponent armed with a bladed weapon. A good rule of thumb is to never try a kick against a knife-wielding opponent, unless the kick is delivered at close range and is used as a support technique.

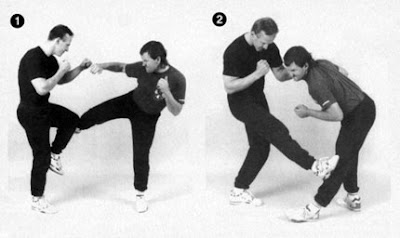

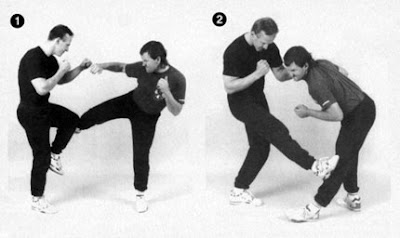

When facing an opponent who attempts (1) a roundhouse kick, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson uses his knee to jam the kick at the shin, then counters (2) with a hard kick to his opponent’s knee joint.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

When facing an opponent who attempts (1) a roundhouse kick, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson uses his knee to jam the kick at the shin, then counters (2) with a hard kick to his opponent’s knee joint.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

Silat Components

What comprises a good silat system?

The following are some of the key components:

• Efficient entry system.

The style must have techniques that allow you to move quickly and efficiently into close range of your opponent. It must also include training methods that will hone your timing, precision and accuracy when employing those techniques.

• Effective follow-up techniques.

The system must have effective punching and kicking techniques. Heavy-duty techniques such as head butts, knee smashes and elbow strikes must be highly developed. “Finishing” techniques are more effective if your opponent is properly “tranquilized.”

• Devastating finishing techniques. After you have entered into close range and applied a “tranquilizing” technique to your opponent, the next step is to apply a “finishing” technique, such as a throw, sweep, takedown, lock or choke, to end the confrontation. Locking maneuvers will break or render ineffective an opponent’s joint. Choking techniques will produce unconsciousness. Takedowns, throws or sweeps will slam the opponent into the ground or other objects with enough force to end a confrontation.

• Reatistic weapons training.

Most silat systems emphasize weapons training at some point. This training will include realistic contact-oriented drills rather than forms practice and will greatly improve your reflexes, timing, accuracy, rhythm and precision. It’s amazing how quickly practitioners improve when facing a bladed weapon traveling at a high rate of speed.

Silat theory, then, is simple: Enter into close range of the opponent, apply a “tranquilizing” technique such as a punch or kick, and then “finish” the opponent off with a heavy-duty technique such as a lock, sweep, choke or throw.

Silat in the United States

Suryadi (Eddie) Jafri was one of the first to teach pencak silat in the United States, conducting seminars throughout the country in the 1970s and ’80s before returning to Indonesia several years ago.

The well-respected de Thouars teaches silat publicly at his Academy of Bukti Negara in Arcadia, California, and also conducts seminars across the United States each year.

Defending against an opponent’s left jab, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) parries (1) the blow and simultaneously strikes the biceps. Gibson blocks a right cross, countering (2) with an elbow to the biceps. Gibson then applies (3) an armbar maneuver, finishing (4) with an elbow smash to the spine.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

Defending against an opponent’s left jab, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) parries (1) the blow and simultaneously strikes the biceps. Gibson blocks a right cross, countering (2) with an elbow to the biceps. Gibson then applies (3) an armbar maneuver, finishing (4) with an elbow smash to the spine.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

Another fine instructor is Mande Muda pencak silat stylist Herman Suwanda, who divides his time between Los Angeles and his home in Indonesia. Mande Muda is a composite of 18 different silat systems. Dan Inosanto of Los Angeles uses his weekly seminars as a forum to spread silat, as well as other martial arts. Inosanto has studied with de Thouars, Jafri and Suwanda in Indonesian pentjak silat.

He has also worked with John LaCoste, who taught Inosanto kuntao silat, silat, kali and langkah silat of the southern Philippines. Inosanto also trained under Nik Mustapha in Malaysian bersilat. There are actually only a few qualified silat instructors in the United States, and most of them are not easy to find.

If, however, you have the good fortune to undertake the study of silat under a competent instructor, prepare yourself because you are in for an exciting, invigorating exploration into one of the world’s richest and most effective martial disciplines.

By Terry H. Gibson

Sourced from http://www.blackbeltmag.com/archives/585

About the author: Terry H. Gibson is a Tutsa, Oklahoma-based martiat arts instructor who teaches various styles of silat, muay Thai and jeet kune do.

This article first appeared in Black Belt Magazine, 1993.

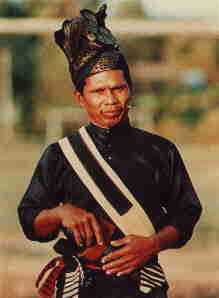

Keris (Photos courtesy of Eddie Jafri)

Keris (Photos courtesy of Eddie Jafri)

In this self-defense sequence, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) scoops (1) his opponent’s jab and simultaneously traps (2) his foe’s other hand in place. Gibson is now free to deliver (3) an elbow to his opponent’s face. Gibson then grabs (4) his adversary’s hair with both hands and pulls (5) his head into a knee smash. (Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

In this self-defense sequence, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) scoops (1) his opponent’s jab and simultaneously traps (2) his foe’s other hand in place. Gibson is now free to deliver (3) an elbow to his opponent’s face. Gibson then grabs (4) his adversary’s hair with both hands and pulls (5) his head into a knee smash. (Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson) When facing an opponent who attempts (1) a roundhouse kick, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson uses his knee to jam the kick at the shin, then counters (2) with a hard kick to his opponent’s knee joint.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

When facing an opponent who attempts (1) a roundhouse kick, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson uses his knee to jam the kick at the shin, then counters (2) with a hard kick to his opponent’s knee joint.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson) Defending against an opponent’s left jab, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) parries (1) the blow and simultaneously strikes the biceps. Gibson blocks a right cross, countering (2) with an elbow to the biceps. Gibson then applies (3) an armbar maneuver, finishing (4) with an elbow smash to the spine.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)

Defending against an opponent’s left jab, silat stylist Terry H. Gibson (left) parries (1) the blow and simultaneously strikes the biceps. Gibson blocks a right cross, countering (2) with an elbow to the biceps. Gibson then applies (3) an armbar maneuver, finishing (4) with an elbow smash to the spine.(Photos courtesy of Terry H. Gibson)